Not Just a Developer

Beyond SQL vs NoSQL (Part 1)

Exploring DBs: Choosing Between SQL and NoSQL, Understanding Database Internals, and Discovering ACID Transactions

This is the first part of a two-part article. Part 1 focuses on databases and their functionality, while Part 2 will delve into distributed systems and how they handle data.

The latest project I've been working on in my role as a software developer is an intelligent chatbot that integrates with the APIs of one of our products, providing an alternative interface to the product's UI.

After several months of extensive research and iterations, we began to focus the development on a specific use case. As things got more serious, it was necessary to move all the data from the server's memory to external databases. As the project leader, I had to make several decisions: which database should we use? What data model should we implement?

At that moment, after some investigation, I realized how little I knew. Yes, I had interacted with various databases in the past and had read several articles about when to use SQL versus NoSQL. However, there seemed to be multiple types of NoSQL databases, and different websites provided varying information. Additionally, I didn't fully understand what a database fundamentally is. I lacked the essential knowledge and understanding of how a database works.

After a full afternoon of researching the best way to learn about this topic, I decided to read two books—one more theoretical to understand the fundamentals and one more practical. Although there were some interesting courses available, I tend to believe that if you want to delve deeply into a subject, you need to turn to books. The two I identified were: "Designing Data-Intensive Applications" (theoretical, very focused on data and distributed systems) and "System Design Interview" (practical, focused on system design interviews).

Having read both books, I can say that the rabbit hole I was about to enter was much deeper than I thought. Many of the concepts I read about might not be as relevant today since cloud services, which are commonly used nowadays, abstract away many of the problems encountered when systems scale to tens of thousands of requests per second.

Nevertheless, I believe that having a solid foundation is crucial for building knowledge in any field. Additionally, now that I understand the details, I can read the fine print of these cloud services and comprehend the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Database Internals

To understand how a database works, let's start by imagining the simplest possible database. This database stores key-value pairs, consists of one file (known as a log file), and writing to it involves appending "key=value" to the file. The problem arises during reading, which will require iterating one by one starting from the end of the file until we find the most recent value. This process is O(n), which means it becomes unfeasible after a certain number of entries in the database.

What we need is an index. An index is a structure derived from the data stored in a database, commonly used to speed up read operations. The downside is that they slow down writing. As we will see, there is a trade-off between read and write speeds.

A simple implementation of an index could be a hashmap. For those unfamiliar with this, you can think of it as a "map" or "dictionary" variable in any programming language. If our database involves appending to a file, a simple index could be a hashmap stored in memory, mapping the key of the key-value pair we stored to the byte offset in the file where the data is located. When we update the file with a new key-value pair, we also need to update the in-memory hashmap.

As we can see, this adds a small overhead to writing (previously we only appended) in exchange for faster reading. Another small process that adds overhead but is necessary in databases based on this idea is removing old, now duplicated key-values (since there is no "update", just append). This process is called compaction.

Additionally, we see that a requirement for such a database would be that the index fits into the RAM where we store the database. A disadvantage of this implementation is that "range queries" ("I want the values from key 1 to 99") are inefficient since there is no order in the data we store.

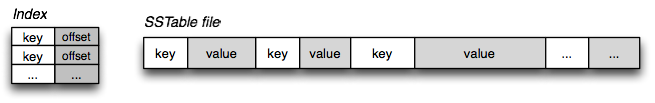

SS-Tables and LSM-Trees

If, instead of just appending, we order the key-values by key, we obtain a Sorted String Table (SSTable). This structure has some advantages over log files with hash maps. These are:

- We don't need to store all keys in memory; we can estimate them through the closest peers.

- The compaction process is simpler.

- It's possible to group key-value pairs and compress them, reducing the I/O bandwidth used.

- Range queries can be executed more efficiently.

Databases that rely on the principles of compaction and merging of multiple segment files are known as LSM (Log-Structured Merge) storage engines.

source: igvita.com

source: igvita.com

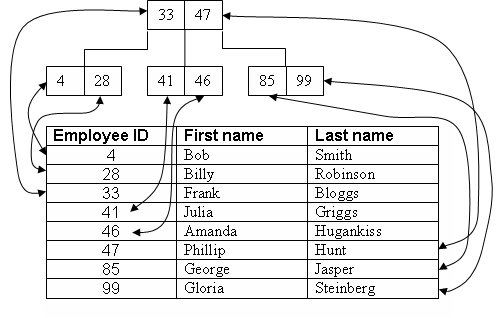

B-Trees

B-Trees are the most common indexes in most relational and non-relational databases. Databases are divided into fixed-size pages (files), traditionally 4 kB, where each page can be identified by a unique address. This allows pages to reference each other, facilitating data organization and access.

In a B-Tree structure, data is organized across multiple levels. The top level is called the root and contains pointers to lower-level nodes. These intermediate nodes, in turn, contain pointers to even lower-level nodes, forming a hierarchical structure. Each layer maintains a certain order, allowing efficient data searches. For example, if we want to find the id=111, the search process could be: 0-1000 -> 100-200 -> 111-135 -> 111. This id acts as an index, which could correspond to a column in the database.

It's important to note that with B-Trees, pages themselves do not change locations. When writing, the affected entries are located and then updated. Additionally, B-Trees are self-balancing, meaning they automatically adjust to maintain logarithmic search time even after multiple insert and delete operations.

Generally, LSM-Trees are faster for writes, while B-Trees are faster for reads. This is because, as we've seen, in a B-Tree, when writing, the exact position of the data must be found and modified, which increases read speed but decreases write speed.

Data Models and Query Languages

Data models are essential because they significantly influence how we think about the problems we are solving.

For those unfamiliar with the basics of SQL/NoSQL, in an SQL database, we have a structured schema of data organized into tables, columns, and rows. Each table contains records, and each record is composed of multiple fields defined by the columns. This structured approach allows for complex queries and maintains data integrity. In a NoSQL database, data is typically stored in documents that contain all the information about an entity and can mix data without a fixed schema.

Using SQL concepts, there are three types of relationships between data:

- One-to-One: A row is linked to 0 or one row in another table. For example, employee - employee details, where details are a column of the employee, are individual, and may or may not exist.

- One-to-Many: A row is linked to one or more rows in another table. For example, employee - employee address, where an employee can have multiple addresses.

- Many-to-Many: A row is linked to one or more rows in another table and vice versa. For example, employee - employee skills, where an employee can have multiple skills, and a skill can be associated with multiple employees.

The data relationship that generates the most debate and can influence the choice between one type of database or another is the Many-to-Many relationship. In SQL databases, we can avoid data duplication through references to other tables with standardized information. Then, with a JOIN operation, we can retrieve all the information in a single query. We will also reduce the likelihood of denormalization, where the same entity has different values, for example in a city field "San Francisco", "SF", and "S. Francisco" .

The challenge with NoSQL databases is that they sometimes do not support JOIN operations, and when they do, they are not as optimized for them as SQL databases. When dealing with Many-to-Many data relationships, NoSQL becomes less attractive. The main arguments in favor of NoSQL databases are:

- Schema flexibility: In a NoSQL database, data with different formats can coexist in the same "location." They are said to have a "schema on read" approach since the schema is applied by the application code. This is particularly useful when dealing with various data types that make it impractical to create a table for each one.

- Better performance due to "data locality": We tend to store all information in a single object, eliminating the need to read from multiple tables. This improves performance at the cost of duplicating data and leaning towards denormalization.

- Data structures closer to application code: The ability to store information with any structure (with nested fields and JSON-like format) allows us to more efficiently save the same data structure as in the code.

Moreover, if we always read all the information of a specific entity (and not different parts in different scenarios), we tend to prefer a NoSQL document store.

We may also prefer NoSQL when dealing with more specific use cases. For instance, when very low latency is required, and we are working with UIDs, it might be interesting to use Key-Value Stores. Another specific use case is when dealing with highly interconnected data, such as in a social network. For these types of scenarios, "Graph DBs" are commonly used.

Transactions

Last but not least, let me introduce a concept I discovered while reading "Designing Data-Intensive Applications": transactions. Transactions address several issues related to the fact that many things can go wrong during an operation. Database software can fail, concurrency issues can arise, network failures can occur, and so on. If an error occurs partway through making multiple changes, it’s difficult to know which changes have taken effect and which haven’t. The application could try again, but that risks making the same change twice, leading to duplicate or incorrect data.

Transactions provide a way to group reads and writes into a single logical unit. Conceptually, all the reads and writes in a transaction are executed as one operation: either the entire transaction succeeds (commit) or it fails (abort, rollback). With transactions, error handling becomes much simpler for an application, as it doesn’t need to worry about partial failures.

These safety measures are often described by the acronym ACID: Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability:

- Atomicity: Refers to the property that operations within a transaction are all completed or none are. There is no intermediate state.

- Consistency: Ensures that a database remains in a correct state before and after a transaction.

- Isolation: The result of a transaction is the same as if all its operations had run serially (one after another), even though they may have run concurrently in reality.

- Durability: Once a transaction has committed, the data will not be lost, even if the database crashes.

There are various levels of isolation. The most basic level, available in almost every database, is "Read Committed." It guarantees two things: we only read data that has been committed (no dirty reads), and we only overwrite data that has been committed (no dirty writes).

While this basic level of protection is good, it does not protect against many other situations that can also occur. A more advanced level of protection used for backups and long-running queries (such as analytical queries) is Snapshot Isolation.

A common workflow is the "read-modify-write" cycle. If two simultaneous transactions perform this cycle, one of the updates can be lost. This is known as a "lost update." To minimize such issues, several approaches can be taken. One approach is to use update operations provided by the database (such as an increment operation for a counter, which is very common). Another approach is the use of locks, where we explicitly tell the database to lock a row so that no one else can read it until we are finished.