Not Just a Developer

Beyond SQL vs NoSQL (Part 2)

Learning About Distributed Systems

This is the second part of a two-part article. Part 1 focuses on databases and their functionality, while Part 2 delves into distributed systems and how they handle data.

In this article I will cover the following topics:

- Basic properties of distributed systems

- Replication

- Partitioning

Reliable, Scalable and Maintainable

Before diving into more specific topics, it's important to understand the basic properties used to evaluate any distributed system. These are: Reliability, Scalability, and Maintainability.

A system is considered reliable when it continues to function even when things go wrong. The issues that can arise are known as "faults," which are defined as "one component of the system deviating from its specification." Our goal is to design systems that are "fault tolerant," meaning they can handle these faults and prevent them from causing "failures" (where the entire system fails).

Next, we have scalability, which is often a primary goal for developers. Scalability is the ability of a system to handle an "increased load." To measure this load, we use load parameters such as requests per second, read/write ratios of the database, etc.

A commonly used metric is "response time," which is the time a client perceives between making a request and receiving a response. We often work with percentiles of response time, such as the 50th percentile (P50), which represents the median response time. For example, if the P50 is 200 ms, it means half of the requests take less than 200 ms and the other half take more. Other common percentiles are P95, P99, and P99.9.

These percentiles are used in Service Level Agreements (SLAs) to determine when a system is considered UP or DOWN. It's typical to consider a system up if P50 is less than 200 ms and P99 is less than 1 second. An interesting fact is that Amazon observed a 1% decrease in sales for every 100 ms increase in response time. Amazon specifically aims for the 99.9th percentile because achieving 99.99 (1/10,000) is too costly. Reducing very high percentiles is challenging because it involves dealing with outliers.

Scalability can be achieved through "scale up" (vertical scaling), where we improve the power of our machines, or "scale out" (horizontal scaling), where we add more machines with the same power.

With the advent of cloud computing, the concept of "elasticity" has gained importance. This allows the system to automatically add and remove resources based on the workload, which is particularly useful for systems with high and unpredictable loads.

Finally, there is maintainability. Sometimes we focus too much on the first two properties and forget the importance of the third. A system is maintainable if it has these three properties: operability (easy to run), simplicity (easy to understand how it works), and flexibility (easy to make changes).

Replication

Replication is the process of maintaining a copy of data across multiple machines (replicas) connected through a network. This is done for three main purposes:

- Reduce latency by keeping data geographically closer to users.

- Increase availability by allowing systems to function even when some parts fail.

- Increase read throughput by scaling out the number of machines that serve read queries.

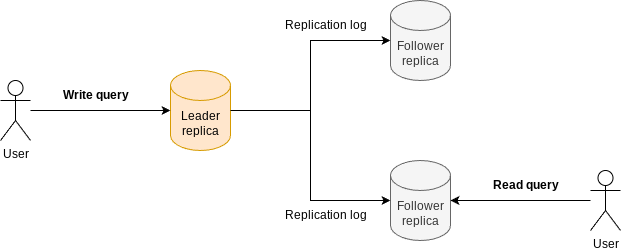

There are several types of replication, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The simplest form is known as leader-based replication (also called active/passive or master/slave). In this setup, one replica acts as the “leader" and clients send write requests to this leader, which writes the data locally first. The other nodes are “followers”; after the leader writes the data locally, it sends the data to the followers (this process is known as the replication log). Clients can then read from any replica.

There are different ways to implement the replication log. One method is to send the same request received by the leader so that the replicas re-execute the query (statement-based replication). Another method is to specify the changes that need to be made to the replicas (WAL and logical row-based replication).

An important replication classification is if it is synchronous or asynchronous. Replication is considered synchronous when, after a write operation, the leader waits for the followers to confirm they have received the replication log before returning an acknowledgment to the client. If the leader does not wait, it is considered asynchronous replication. The main advantage of synchronous replication is that the followers always have the same data as the leader (strong consistency). The downside is that if even one follower is down, the system cannot process write operations. Conversely, asynchronous replication allows the system to continue processing writes without waiting for all replicas to be available (eventual consistency).

An important parameter in systems that use replication is the replication lag. This indicates the time that passes between the leader receiving a write request and the follower reflecting that change.

Multileader Replication

When we allow more than one replica to accept writes, we have multi-leader replication (also known as master-master or active-active replication). Each leader acts as a follower to the other leaders. In this case, synchronous replication between leaders would be counterproductive as it would be equivalent to having a single leader in terms of latency.

Multi-leader replication makes sense in specific scenarios, such as:

- Multi-datacenter deployment: Useful for reducing latency by having leaders in different geographic locations.

- Clients with offline operation: For example, a calendar app on mobile/laptop devices, where each device has its own database acting as a leader and replicates asynchronously when it has internet access.

- Collaborative editing: Similar to Google Docs, where multiple users can edit the same document simultaneously.

The primary challenge with multi-leader replication is not just consistency issues but also the potential for conflicts when the same data is modified concurrently in different leaders. A simple strategy to avoid conflicts is to designate a specific leader replica for each record, ensuring that all writes for that record go to the same leader.

When conflicts do arise, they can be resolved using various strategies:

- Using a timestamp: Last Write Wins (LWW).

- Assigning more authority to certain replicas.

- Merging the values: For example, concatenating changes.

- Storing conflicts in a data structure and writing application code to handle them: for instance, notifying the user to resolve the conflict. Most databases support writing an “on conflict handler.”

Leaderless Replication

When all replicas can accept writes, it is known as leaderless replication. Amazon Dynamo famously introduced this type of replication as the default.

In this architecture, when a client writes or reads data, it sends the request to multiple replicas in parallel. To detect "stale records," version numbers are used. When writing, it is not necessary to wait for acknowledgment from all databases.

There are several approaches to data propagation in this type of architecture. Typically, the client sends the write to multiple nodes, and those nodes then propagate the write to additional nodes.

Traditionally, when a replica goes down and then comes back up, there are two main ways for it to catch up:

- Read repair: When a client with the latest version of the data detects a stale record, it sends an update to the replica. This is effective for frequently read entries as stale records are detected quickly.

- Anti-entropy process: A background process that searches for differences between the data on different replicas.

In this type of replication, we achieve what is known as quorum consistency. As mentioned earlier, when a client writes data, it does not wait for acknowledgment from all replicas. If there are n nodes, the client usually waits for acknowledgment from w replicas when writing and from r replicas when reading, such that w + r > n. This ensures that we always get an up-to-date value.

For example, if there are 3 replicas, with w=2 and r=2, we make sure that at least 2 replicas have received the write. Then, when we read, we only need to wait for 2 replicas to respond. One might have a stale record, but the other will have the updated one, and we can detect which is correct using versioning.

Leaderless replication is interesting when we need high availability and low latency, at the cost of slower reads and occasional stale records. It is important to remember that w and r just help us adjust probabilities, but do not provide a complete guarantee that we will never read a stale record.

Partitioning

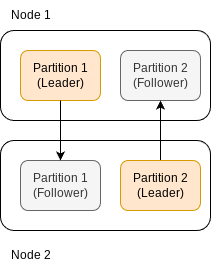

Large datasets and high query throughput require data to be split into partitions (or shards). This is usually combined with replication, where each partition can be the leader of certain partitions and follower of others.

One of the biggest challenges in partitioning data is ensuring that all partitions receive an equal load. Uneven distribution leads to "skewed partitioning" where some partitions, known as “hot spots,” handle more load than others.

Data Splitting Strategies

Two examples of splitting strategies are:

- Range-based Partitioning: Assigning a continuous range of keys to partitions (like volumes of an encyclopedia). While this allows us to know exactly where a specific key is stored based on its range, it can easily result in skewed partitioning if key distribution is uneven.

- Hash-based Partitioning: Using a hash function to distribute keys evenly across partitions. This method ensures even distribution but sacrifices the ability to perform efficient range queries.

An interesting algorithm used to decide data to node assignment (which I will not touch on this article) is consistent hashing.

Request Routing Without Primary Keys

A big challenge regarding partitioning is: How can we route requests when data is not accessed using its primary key? There are 2 main approaches:

- Document-based Approach: Each partition maintains its secondary indexes. Writes are directed to one partition, while reads query all partitions. The downside is that reads can become expensive.

- Term-based Approach: A global index is distributed across nodes. For instance, a partition might store an index for car colors ranging from “a” to “f,” pointing to the primary keys of cars with those colors, which may be stored on different partitions. This makes writes more expensive.

Rebalancing Partitions

Periodic rebalancing of partitions is crucial to maintaining efficiency and performance. Rebalancing redistributes data across partitions to ensure an even load, preventing any single partition from becoming a bottleneck. There are two common approaches:

- Fixed Partitioning: The number of partitions and key-to-partition assignments remain constant. During rebalancing, only the assignment of partitions to nodes changes.

- Dynamic Partitioning: Particularly useful with key range partitioning. Partitions are split into two when they exceed a certain size, and the new partitions may be reassigned to different nodes.

Request Routing

Clients need to know which database node to connect to, a problem that falls under the broader category of “Service Discovery.” There are three primary approaches:

- Clients can connect to any node: if the node doesn’t have the data it forwards to the appropriate node and it handles the response.

- Clients send requests to the routing tier: it determines the node, it is a “partition aware load balancer”

- Clients are aware of partitions and assignments: they know which node to connect to

What changes in each case is the routing component. How does this component learn about changes? We usually have a separate service such as Zookeeper that holds this data. Nodes notify changes to this service, and the routing tier consults this service to be up to date.